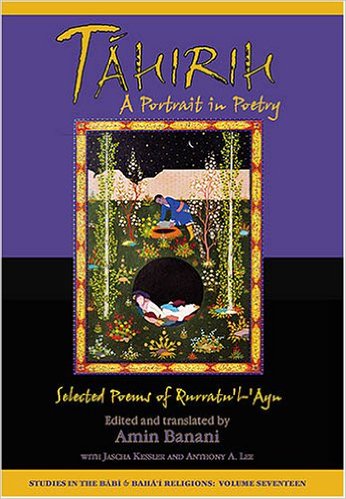

Táhirih: A Portrait in Poetry, Selected Poems of Qurrat’ul-‘Ayn

edited and translated by AMIN BANANI, JASCHA KESSLER, and ANTHONY A. LEE

Review by SANDRA LYNN HUTCHISON

Who was Táhirih? How do scholars understand her life and her achievement today? Among recent books that claim to unveil the truth about of a woman who remains one of most enigmatic figures of nineteenth century Iran, perhaps none offers a more vivid portrait than does Táhirih: A Portrait in Poetry, Selected Poems of Qurrat’ul-‘Ayn, which tells her story in her own words.

Published in 2005 by Kalimat Press, this book showcases 23 of Táhirih’s best-loved poems, as translated by Amin Banani with Jascha Kessler and Anthony Lee. Comprising songs, lamentations, prayers, and ecstatic outpourings, the poems range, in tone, from triumphant to despairing. At times energized by accounts of experiences of spiritual ecstasy, and, at other times, freighted with raw human emotion, these poems are the voice of Táhirih as she speaks to the reader, revealing much about her multi-faceted life as a poet, woman, mystic, scholar, revolutionary, activist, and feminist.

And it is the very richness of this life, fuelled as it is by what Banani describes as “her tempestuous temperament,” with its contradictory impulses—to transcend the world or to become embroiled in its struggles?—that makes Táhirih a source of fascination for so many readers.

The portrait these 23 poems paint avoids the kind of hagiographic depiction common to some attempts at recreating Táhirih’s remarkable life, for in the poems, her expression of religious ecstasy is framed by the particulars of time and place and by the complex of motivations that guide every human being, no matter how single-minded, through everyday life.

In Táhirih, we have a figure as magnificent and as doomed as a hero from Greek tragedy. How can a woman who is reputed to have thrown off her veil to proclaim the rights of women, hope to survive in nineteenth century Iran? How can the daughter of a Muslim cleric dare to claim that she has met the Promised One, the Qa’im, in a dream? Just how did a woman in that draconian century of Iran’s history summon the courage to defy not only social convention, but also her family and the clergy in order to proclaim the dawn of a new day for women as well as the advent of a new religious dispensation?

And if, like tragic heroes, Táhirih has a fatal flaw, some hamartia, it is her sheer single-mindedness, her obsessive love of God and her passionate devotion to the figure of the Bab, the “Gate,” as he proclaimed Himself to be, that One who would prepare the way for “He Whom God Shall Make Manifest”—Bahá’u’lláh.

In “Just let the wind. . . ,” for example, Táhirih shows herself to be master of the passionate and extravagant gesture, characterizing herself as a kind of spiritual harlot, someone so transformed by the love of God that if she were to show her true beauty, the world and everyone in it would be irresistibly drawn to it:

Just let the wind untie my perfumed hair,

my net would capture every wild gazelle.

Just let me paint my flashing eyes with black,

and I would turn the day as dark as hell.

Yearning, each dawn, to see my dazzling face,

the heaven lifts its golden looking glass.

If I should pass a church by chance today,

Christ’s own virgins would rush to my gospel.

“Point by Point,” which is perhaps Táhirih’s best known poem in its original language, speaks more powerfully than does any other poem in this volume to the spiritual triumph achieved by complete surrender to the Beloved. In the opening verses, the poet begs for reunion with the lost Beloved:

If I met you face to face, I

would retrace—erase!—my heartbreak.

pain by pain,

ache by ache,

word by word,

point by point.

In search of you—just your face!—I

roam through the streets lost in disgrace,

house to house,

lane to lane,

place to place

door to door. . . .

And in the final stanzas of the poem, Táhirih celebrates her much-sought after reunion with her Beloved:

While I grieve, with love—your love! I

will reweave the fabric of my soul,

stitch by stitch,

thread by thread,

warp by warp,

woof by woof.

Last, I—Táhirih—searched my heart, I

looked line by line. What did I find?

You and you,

you and you,

you and you.

The despair of separation—how can any lover ever be close enough to her Beloved?—and the hope of reunion shapes another of the poems in this volume, “My Head in the Dust,” into a heart-rending lament that is also a passionate love poem. Here are the opening stanzas:

I will lay my head in the dust before your face.

My idol, this is the holy law I embrace.

You are the Ka’aba that I long to circle ‘round

A river of tears falls from my eyes to the ground. . . .

Finally, in “Look Up!”,a poem Banani refers to as a “manifesto” and “anthem,” we see Táhirih at her most powerfully prophetic. Here is a woman who is fearless and unwavering in her commitment to proclaim the teachings of her new-found religion:

Look up! Our dawning day draws its first breath!

The world grows light! Our souls begin to glow!

No ranting shaykh rules from his pulpit throne

No mosque hawks holiness it does not know

No sham, no pious fraud, no priest commands!

The turban’s knot cut to its root below!

No more conjurations! No spells! No ghosts!

Good riddance! We are done with folly’s show!

The search for Truth shall drive out ignorance

Equality shall strike the despots low

Let warring ways be banished from the world

Let Justice everywhere its carpet throw

May Friendship ancient hatreds reconcile

May love grow from the seed of love we sow!

What has always struck me, as a Western reader as well as an English-language poet nurtured in the school of free verse and all that goes along with it, is just how challenging it must be to work in a poetic tradition so laden with literary conventions that must be respected. For me, one of the great mysteries of classical Persian mystical poetry is that its practitioners manage to find their voices as poets within the context of a tradition that seems so restrictive, with form, imagery, and rhythm already prescribed.

Yet Táhirih succeeded. Working within the time-honored practices of esteqbal and tazmin, the poetic forms and rhythms of classical Persian verse, and the conventional imagery and symbolism of Persian classical poetry, she managed to forge a strikingly original voice and vision.

Amin Banani’s scholarly introduction to this volume and his voluminous and erudite notes serve as a gloss to the poems, offering elucidation on their literary and historical contexts as well as information about some of the less well known aspects of their making, transmission, and preservation. From Banani, we learn about where the poems fit in the tradition of Persian mystical poetry, about the complex history of the manuscripts that constitute the body of Táhirih’s work, and about the difficult personal decisions that serve as the backdrop for her literary expression.

Without doubt, firsthand accounts by authors of their own lives are invested with a special potency and ignite a certain fascination in any reader who wants to understand the inner workings of an author’s mind, and so the poems of this volume carry within them the power of truth and also the draw of intrigue. And for the Persian reader, the text of the poems in their original language is displayed on opposite pages. This book is a treasure, and one worthy of discovery by any reader interested in entering into the life of this remarkable figure.