Thy Court of Holiness

by MAHSA FOROUGHIAN

Amidst the desolate, proud mountains in the north of Iran, where the Haraaz and Nour rivers meet, there lies a road named Balaadeh Road. The road is tight and sharp. On the right, there is the steady hand of the Alborz mountains, welcoming and guiding visitors to their destinations. And on the left, there is the warm yet fresh embrace of the river. As the road continues, the number of cars lessens, and there comes a point where I find that my friends and I are the only people traveling along Balaadeh Road. Only the bright blue river, the verdant mountains, and the snowy summits are our companions; the calm and peace they exude soothes our souls.

We pass through villages and burghs, and before long our majestic destination begins to reveal itself. Though small, this village holds great memories in its heart. Takur once belonged to a remarkable man named Mirza Buzurg Nouri. He was one of the viziers in the court of the Shah of Iran. Mirza Buzurg spent most of the summer days in Takur with one of his sons, who was most dear to him and whom he kept very close. Today, the world knows this beloved son of the vizier as Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith.

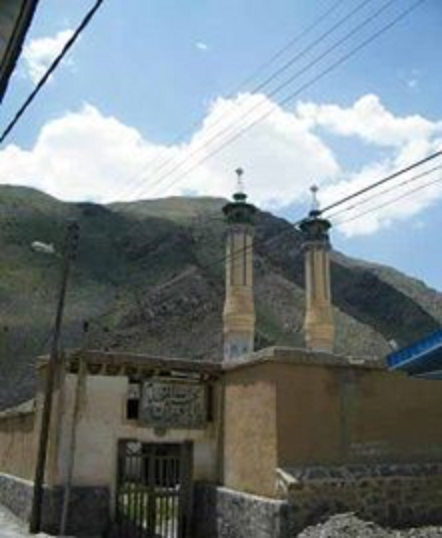

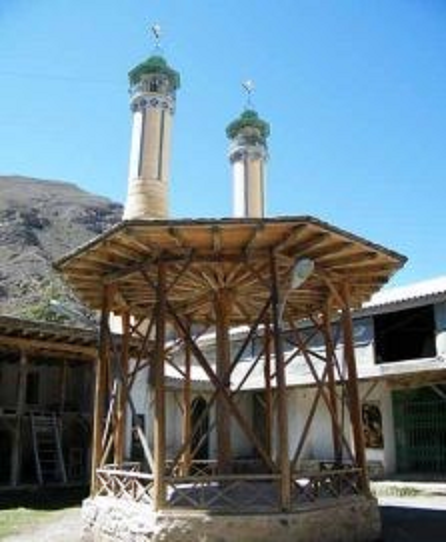

I bend, lower my head, and walk into the backyard of the mosque. I straighten my head, squint to adjust to the light, and take a quick look around. I feel as if I am walking into a new world. The yard is square and covered with long yellowish grass. Fourteen vaults are positioned around the yard. At the center of the southern side of the yard, six wooden steps lead to a balcony.

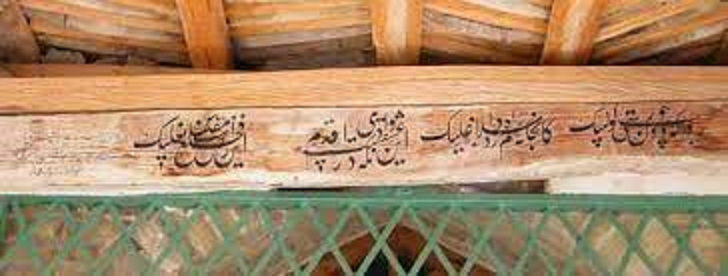

As I survey the structure, my eye catches something surprising: an inscription. I did not expect to see this in the mosque. On top of the entrance to the mosque’s central hall, I see the famous poem Mirza Buzurg inscribed on a piece of wood at the gate of the house he built for his son, Bahá’u’lláh:

“Greetings and salutation rest upon this Mansion which increaseth in splendour through the passage of time. Manifold wonders and marvels are found therein, and pens are baffled in attempting to describe them.”

Minutes pass by, and I find myself unable to articulate all I feel in my heart. I choose a corner under a vault in front of the inscription and sit for a moment as I try to imagine what life was like for Bahá’u’lláh as a child in this village. I close my eyes and think about some of the things I remember about His time in Takur: the dreams He had in childhood that revealed His greatness and intelligence to His father, His frequent walks in the beautiful countryside surrounding Takur, the puppet show that inspired Him to ponder the transience of this earthly life. I open my eyes and take another look around and begin to pray:

O Lord, my God! Give me Thy grace to serve Thy loved ones, strengthen me in my servitude to Thee, illumine my brow with the light of adoration in Thy court of holiness, and of prayer to Thy kingdom of grandeur. Help me to be selfless at the heavenly entrance of Thy gate, and aid me to be detached from all things within Thy holy precincts. Lord! Give me to drink from the chalice of selflessness; with its robe clothe me, and in its ocean immerse me. Make me as dust in the pathway of Thy loved ones, and grant that I may offer up my soul for the earth ennobled by the footsteps of Thy chosen ones in Thy path, O Lord of Glory in the Highest.

We hear that the locals are Bahá’ís in their hearts but are afraid to proclaim their faith openly since it since it could mean that their lands and houses would be confiscated. They know we are Bahá’ís and we know they are too. Our mutual knowledge causes us to exchange smiles of warm greeting without uttering a single word. There is a small grocery shop along the dusty road. My friend and I walk toward the shop and she tells me all about the owner: “All the locals here are related to Bahá’u’lláh in one way or another,” she says. “Years ago when I was here, the owner of this shop explained to us that he can trace his line back to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.”

When my eyes meet those of the shop owner, I know in my heart that what my friend has told me is true. The man has two gleaming blue eyes, full eyebrows, a compelling smile, and is of medium height. He welcomes us in a friendly voice; it is just as if he has anticipated our coming. Like the other locals, he knows why we are here and why we have chosen to visit his shop, especially when we have no idea what we want to buy. My friend and I look around the store, pass by some shelves, then decide on two packages of biscuits. The store keeper does not know how to read, so he asks us to tell him the price of our biscuits. We pay what we owe. But before leaving the store, we look deep into his blue eyes, and in them, we see something of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá!