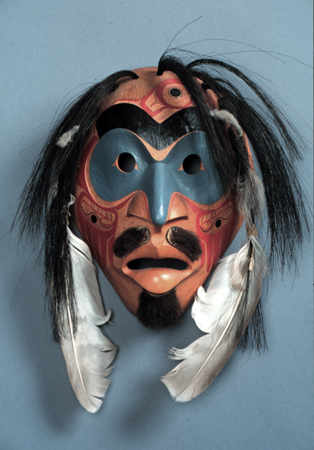

“Shaman’s Mask” by Jim Schoppert

Editorial: Art as a One Eared Mad Man

Art, whether literary or visual, thrives in that uniquely productive ecosystem established when the imagination of the artist becomes deeply connected to a place. Whether it be Flannery O’Connor’s Georgia, Alice Munro’s Ontario, or Richard Russo’s New York — when the imagination of a gifted artist takes root in a region, the art that results can be unforgettably particular and, at the same time, profoundly universal. When keenly observed and deeply imagined, “here” becomes “everywhere.”

So it is that a mask made by Native woodcarver Jim Schoppert can draw on the traditional art forms of the Chupagh people to pay fanciful tribute to the iconic modernist painter Vincent Van Gogh, who is thought to have cut off his ear in a fit of madness. “Art is a One-Eared Mad Man” is a mask that could not have been made by anyone but Schoppert, an Alaskan Native carver at ease with traditional forms but also visionary enough to innovate upon and thus extend them so that they might reach lovers of contemporary art. In this issue of e*lix*ir, we are pleased to share images of a wide range of Schoppert’s works, in different styles and media.

In Schoppert’s view, the art of his own people, the Tlingit, “comes . . . from that very strong mystical relationship with the land.” Blessed is any place where the spirit might commune with the land, for it is in those rural spaces that art grows, sometimes wildly and with vigor reminiscent of a weed — the bright dandelions of art. Witness the remarkable body of twentieth century paintings inspired by the landscape of Provence, Van Gogh’s among them. It seems clear, too, that the poetry of the Romantics could not have come into being without England’s Lake District.

Not just wild, untrammeled spaces, but the vibrant and distinctive communities that grow up in proximity to rural spaces also serve as sites where regional art can thrive, such as that pioneered by Maine writer Sarah Orne Jewett, whose work is explored in this issue. Indeed, is there any kind of art other than regional art? Is there any kind of vibrant community other than the “local” one? Even in a global society, particularity must be the ground in which the seeds of art are sown. Unity in diversity. Diversity in unity. A plurality of art forms, as inspired by time and place, will, no doubt, save the art of the future from becoming prescriptive, like Soviet art under Stalin or Chinese art under Mao, or from becoming the art of a global monoculture.

Is there any other kind of art than regional art? The question invites reflection. I believe that the artwork presented in this issue of e*lix*ir answers that question. In the case of long-time Bahá’í Jim Schoppert, an ancestral as well as a visionary connection to the haunting landscape of Pacific Northwest inspired a widely recognized body of original work that, as Ray Hudson explains in his article on Schoppert, draws upon tradition as a point of departure for innovative work that evokes the world-embracing vision of the Bahá’í Faith.

Though they both hail from Maine, poets Patricia Ranzoni and Lynn Ascrizzi inhabit different imaginative landscapes — Ascrizzi the world of the garden and cultivated field, and Ranzoni the world of a quiet mill town. Ranzoni’s poems are both elegy and call, an elegy for a way of life built around the economy and culture of paper making, and a call to the people who lived this life, to reinvent themselves now that the mill is still.

Hailing from the woods and pasturelands of Southwestern Ontario, poet Monte Schooley sets down a record, vividly imagined, of an almost vanished world in which people lived close to the land in tight-knit rural communities where the rhythms of planting and harvesting forged powerful bonds.

In the fiction section, an excerpt from Ray Hudson’s forthcoming Young Adult novel, Ivory and Paper, offers a powerful argument for the importance of a strong sense of place in the creation of art. Hudson’s three decades on the Aleutian Islands left him not only with this story to tell, but also with skills as a woodblock carver and enough experience for a compelling memoir that evokes life as it once was in a traditional seal hunting community. Prints made from Hudson’s woodblock carvings appear at the top of various pages of this issue.

In “Looking Back on Books,” we review Hudson’s memoir, Moments Rightly Placed, and also Frank Lewis’s translation into English of Zoya Pirzad’s award winning novel Things We Left Unsaid, which offers yet another vivid evocation of a particular time and place — a middle class suburb in Abadan, a major oil refining city in the southwest of Iran, in the 1960s.

My own musings on Sarah Orne Jewett’s Maine flesh out the essay section, and in “The Voices of Iran” section, we feature Saba Shadabi’s lyrical reflections on her father’s house in the Markaz district of Kermanshah, Iran. “A Small Piece of Heaven on Earth” gives a fascinating glimpse of a still very hidden country, a place known to Bahá’í readers primarily as the site of the persecution of their fellow believers. But Saba’s essay offers a different view — of a small haven of domestic life, an oasis of peace in a land of enormous beauty. Saba’s essay may well remind such readers of the great station of this beleaguered country, especially of its capital city, as expressed by Bahá’u’lláh:

Let nothing grieve thee, O Land of Tá (Tihrán), for God hath chosen thee to be the source of the joy of all mankind.

Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh , p. 110.

Finally, in “The Writing Life” section, I reflect on what I learned at Bill George’s Little Pond Arts Retreat about the role of prayer and meditation in the artistic process. In “A Prayer in Nine Postures,” I offer the results of an experiment undertaken during that retreat in which a Bahá’í prayer served as the wellspring for a poem. Such experiments represent steps along the path towards a new aesthetic in which artistic practice might merge with spiritual practice.

Imagination, a spirit of praise, and a deep connection to place — ingredients of a potent elixir with the power to transform the most ordinary of experiences into extraordinary art.

— S.L.H.